I’ve been talking a lot about Stampede these last few months. I’ve wondered how artists navigate their creativity and practice during “The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth.” I’ve dubbed these conversations “Creatively Cracking the Stampede Code.” The question being, how do artists Stampede? How do they find themselves within this overwhelming cultural event that grips the city for 10 days?

AN OPPORTUNITY

We artists are aware of that dangling monetary carrot Stampede offers. The trick is finding a balance between making the bank and being crushed by 10 days of corporate patronage. Actor, producer, writer, and teacher Linda Kee is fully aware of this balance.

“The big picture answer is to sit in the constant tension between, not just two, but all opposing forces,” says Kee. “Because it is my job as an artist to constantly creatively problem solve. Depending on where you live, Stampede can feel like an invasion of your neighbourhood. There’s the garbage, traffic, people, and increased aggression. But if I pour drinks for 10 days, and it pays my rent for three months, I can freely work on my creative writing. Because ultimately, the question becomes how do I want to spend my time?”

The answer constantly changes from artist to artist, but clarity is required for the navigation and a finely edged negotiation between comfort and freedom.

“It’s a negotiation that I think any artist who knows who they are knows well,” says Kee.

“We know we can’t close ourselves off from the opportunity to make ends meet, trying to live and breathe in this city.”

IT’S COMPLICATED

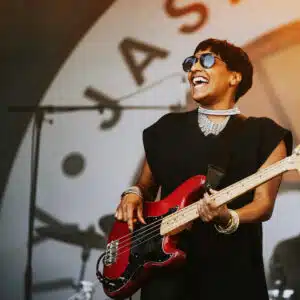

Lisa Jacobs is a music therapist and bassist known for owning the low end at the legendary Stampede Grandstand Show stage.

“The Grandstand band has become intentionally more diverse over the years,” says Jacobs. “There’s been this desire to open up the stage to reflect more of what our city looks like. This is important to consider because we’ve seen how the Stampede seemed to be predominantly white industries and spaces. But when we talk about Stampede, we aren’t just talking about Stampede: we’re talking about how important it is to be aware of all the different elements that bring people together and create a sense of community.”

Engaging with Stampede enables many opportunities for artists that aren’t necessarily monetary. It is the opportunity to find and lose oneself simultaneously. Hold onto your hats and hold onto your values.

“I don’t think every artist has to have the same values as me,” says Jacobs. “Service, expression and support … they’re [my values] and Stampede highlights the complexity of having values and living from them. You always have to negotiate it, and it’s not easy. But every time I choose to be involved with something, be it Stampede or anything to do with the history of this country, I ask myself, ‘How can I do this in a way [so that] that I’m good with myself?’”

FAMILY TRADITIONS

Autumn EagleSpeaker is what you might call “Stampede OG.” She is a Blackfoot Kainaiwa/ Black artist, burlesque performer, executive director of Making Treaty 7, and co-founder of Authentically Indigenous Inc.

“I came to Stampede initially as the wide-eyed teenager,” says EagleSpeaker. “Eyes glazed over like mini donuts, but all the traditions were really important to me. Sitting in the same place every year for the parade, pancake breakfasts and then living in a tipi or an RV for ten days on the grounds. Our whole family would be there: cousins, uncles, aunties, and elders. I missed that when I stopped going, the whole vibe of the family being there together. Our family stopped going after my grandfather died in the mid 1980s. It wasn’t the same as when he was alive and I hadn’t gone as a child, because my grandmother didn’t want to attend anymore. But all my older cousins and uncles and everybody, they have really big Stampede memories of just being there, participating and doing all the things. So for me, it’s about carrying on that family tradition, honouring our loved ones, and promoting our culture in the way that we weren’t allowed to.”

Many Stampede relationships are built on familial memories. Kee searches for a window every Stampede night, transporting her to when she and her brother — the late, great Marvin Kee — lived in a house right off Scotsman’s Hill, the city’s prime fireworks viewing location. Jacobs continues to attend the same Stampede breakfasts she did as a kid. And EagleSpeaker’s lineage stretches back to the beginning days. Her auntie and family member, Evelyn EagleSpeaker, was the first Indigenous Stampede Queen in 1954.

I’m not alone in attempting to hold onto multiple truths when considering what Stampede means. But that doesn’t mean we can’t enjoy the fireworks.

Kenna Burima is a Calgary-based songwriter, musician, mother and teacher.