Also known by her spirit name, Night Singing Woman, Autumn Whiteway is a Saulteaux/Métis artist, curator, archaeologist, and member of Berens River First Nation. Her multidisciplinary practice blends Indigenous identity, ecological awareness, and resistance to colonial narratives — often through the vivid lens of Woodland-style art and photography.

Her work has been exhibited at venues such as Werklund Centre (formerly Arts Commons), cSpace, the Calgary Central Library, Contemporary Calgary, and more. She currently delivers Arts ReimaginED workshops for students, supporting creativity and inclusion.

OUTSIDE THE BOX

“What I’ve seen through Arts ReimaginED is that there’s a real need for this kind of programming. Some students — often those who don’t usually show up for class or are considered neurodivergent — engage in these arts programs.

“I’ve had teachers say their students stayed through the entire day and really enjoyed it, whereas typically they wouldn’t participate. Arts in general just have a huge impact on students. It’s a different way of learning.

“When I work with students, I let them know they can apply Woodland Style to anything — a video game character, their favourite animal, even their favourite food or sport.

“There aren’t strict rules, just the general principles. And I find many students are blown away by that. They’re used to working inside the box.”

NORVAL MORRISSEAU

“The Woodland Style was developed by Norval Morrisseau, who was an Anishinaabe man from Ontario. He created the style in the 1960s. It’s a very colourful style, filled with symbolism.

“It’s thanks to Norval Morrisseau that a lot of Indigenous artists have the opportunities they have today — to be shown in galleries, to be recognized — because before that, Indigenous art was often displayed as though Indigenous people were no longer living.

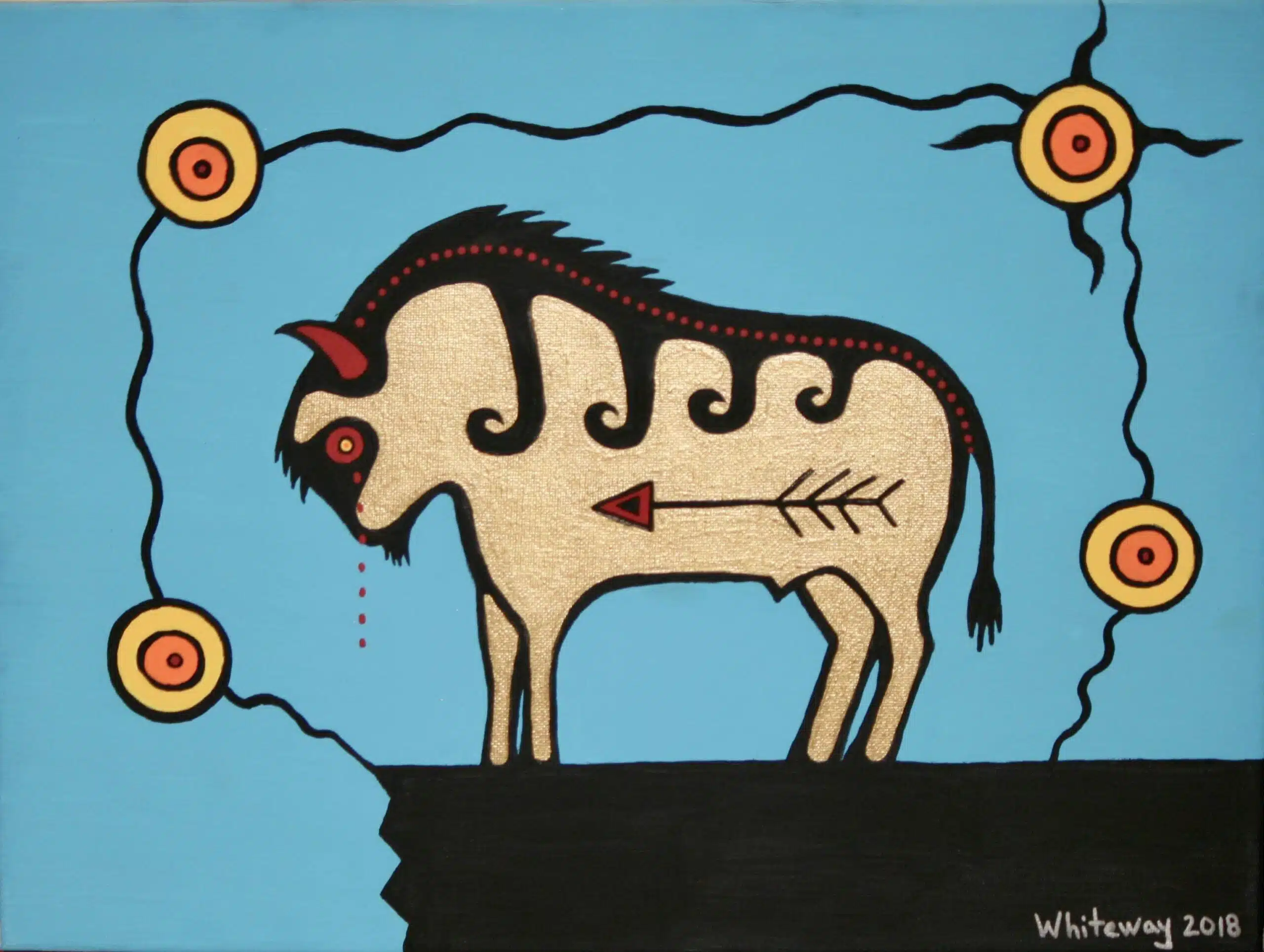

“Some of the defining features are heavy black outlines. There’s often an ‘x-ray’ effect, where you can see skeletons or inner parts of figures. And there are shapes within shapes that define parts of the body or tell part of the story.

MANY DIFFERENT PLACES

“I often work archaeological things into my artwork. For example, I have one piece called All My Relations — it’s a digital drawing, and I’ve included a lot of different rock art that’s found in Alberta. Another one is Bloodlines, which shows a bison standing at the edge of a buffalo jump, crying blood tears because it can no longer offer itself as food for the people.

“I think it [the most inspiring] would be my journey through Central Asia, especially Mongolia. I remember seeing these standing stones and just feeling this energy coming from them — very similar to the energy at Majorville Cairn and Medicine Wheel in Alberta.”

PIXEL BY PIXEL

“I’ll have a vision or a daydream that comes to me randomly — something I’d like to create.

“Each medium has a different process. My photography, for example, probably takes the most time. One of my pieces at Arts Commons took a month to prepare: I created a huge digital banner, got models and period costumes, gathered or made props — a lot of prep work.

“My digital art takes forever because I zoom in and work pixel by pixel — I’m a perfectionist.”

AUTHENTIC REPRESENTATION

“It’s when Indigenous people represent themselves. Self-representation is key — it should guide how Indigenous people are shown in art and media.

“A lot of artists rely on funding, and funding agencies often have this idea of what ‘Indigenous art’ is supposed to be. If you stray outside that box, you might not get funded, so artists stay in the box.

“As a result, a lot of creative work never gets made. People expect something like a chief in a headdress on a horse looking off into a sunset. Those are the clichés.”

BUILDING DIALOGUE

“I just go with my gut, with what I need to express. I don’t set limits or ask others if it’s ‘appropriate.’ For me, it’s a way to process intergenerational trauma. I’m not that eloquent with words, but when I sit down and build these pieces, the images speak for me.

“Sometimes I choose a theme because I want to highlight Indigenous issues and realities. I want to foster dialogue between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

“There’s been a real shift, especially since the pandemic and the discovery of the 215 children in Kamloops. It raised a lot of awareness and brought people to the table. Indigenous voices are being included in more conversations, and I think the future is bright — if we keep those conversations going and work together respectfully.”

QUICK TAKES

Major inspirations: Norval Morrisseau, Kent Monkman

As a Curator: “What always draws me is story. Sometimes a piece looks simple but has deep symbolism or narrative behind it.”

What’s Next: “I’m working on a large mural in the Woodland style using Lego bricks. It really takes me back to childhood, and it’s just fun.”

This Q&A was created in collaboration with Werklund Centre.

To see Autumn Whiteway’s work, visit autumn.ca.